You Don't Need Story Points

3 minute read

In my last 5 Minute DevOps, I attempted to define user stories in a testable way. Real developers should test, after all. Now that we have a story, how do we communicate when it can ship?

We have a long history of attempting to communicate the uncertainty of outcomes to non-technical stakeholders. We speak in delivery probabilities, not certainty. It can be frustrating to those who don’t understand, but software development is not cookie cutter and managing expectations is key when uncertainty is high.

T-shirt sizing, ideal days, and story points have all been used in an attempt to communicate how complicated or complex something is and our certainty of the date range we can deliver on. However, the issue they all share is that they leave much to interpretation. This in turn leads to hope creep as stakeholders start planning optimistic dates.

Story points are particularly troublesome. Teams just starting out will equate story points to hours or days. External stakeholders will do the same. Managers will try to “normalize” story points to compare teams’ relative productivity with their velocity, a staggeringly poor metric. In the end, no one sees any real value.

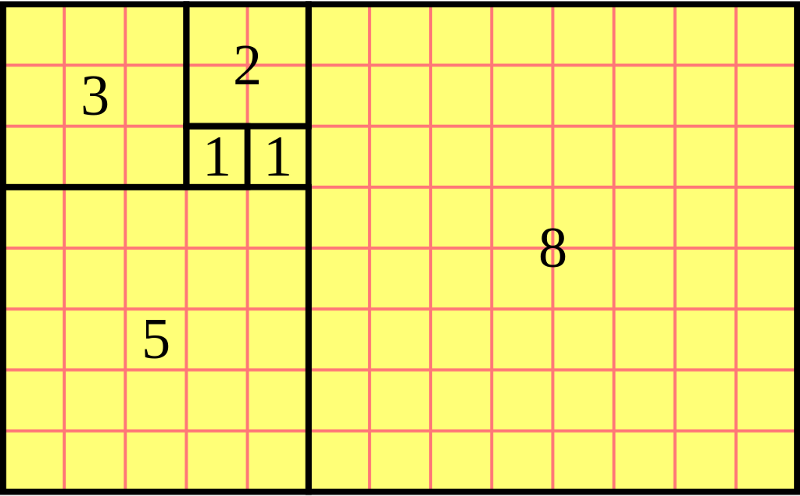

So, what is a story point really? It’s a statement of relative size and complexity compared to a task the team understands and can estimate. You cannot “normalize” them because no two teams have the same knowledge or experience. The bigger the story point size, the less certain and more complex. Uncertainty also isn’t linear. We use the Fibonacci sequence because it increases with the square of the number.

That clear? Good. Now forget it because no value is delivered by continuously improving how we “point” or by spending time in meetings voting on how many story points something is. Time is much better spent in extracting the real requirements by decomposing the work into tasks that can be delivered tomorrow.

One of the key practices of DevOps is decreasing batch size. Not only does this accelerate value delivery, but also reduces the blast radius when we get things wrong. Small change == small risk.

Paul Hammant argues that most stories should be sliced to one day. If you cannot, then you have the wrong people, wrong tech stack, wrong architecture, or just poor story slicing skills. In my experience, all stories can be sliced to less than three days. Any estimate becomes shaky after two. The benefits to clarity of purpose, speed to market, and predictable delivery demand that we aim for small stories.

We’ve seen good results following this process. Small stories make requirements clear, deliver predictably, and resist gold plating, scope creep, and sunk cost fallacy. If we agree that a story can be delivered in two days, on day three we know there’s a problem we need to swarm. If a story is 5 “story points” it’s probably at least a week’s work and we’ll find out in the middle of week two that it’s late, if we are lucky.

Forget story points.

A skilled team can slice stories so that everything is a “1” or a “2”. At that point, all we need do is agree as a team a story can be done in that time range and track the throughput of cards. Anything else is focused on ceremony instead delivery.

If you are using story points, you need to focus less on getting better at “pointing” and focus more on what really delivers value. Decompose work and ship it.

Next time: Are You a Professional Developer?

Written on January 31, 2019 by Bryan Finster.

Originally published on Medium