The Thin Red Line

4 minute read

I was speaking at a DevOps meetup in Finland recently and was asked, “what does DevOps mean to you?” I love that they started the conversation that way. DevOps no longer means Development and Infrastructure teams cooperating and it has never truly been a job or a team. We are not solving a technical problem. We are trying to solve a business problem. How do we more effectively deliver value to our customers?

Note: If someone works for our company, they only become a customer when they buy something from our company.

DevOps is the way we work to improve the continuous flow of value to the end-user. Since our goal is to improve value delivery, we must measure how we deliver value, identify the constraints, and continuously improve the constraints. Everything we do and how we do it must be examined for the value it delivers and be removed if it is not delivering value. This is a long-term process that takes strategy, change management, and constant focus. The reason so many improvement efforts fail is that executives are rarely rewarded for long term improvement. Splashy “Transformation!™” efforts make analysts happy, make good presentations at conferences, and result in job offers. Real improvement requires more than the 2–3 year tenure of many IT executives.

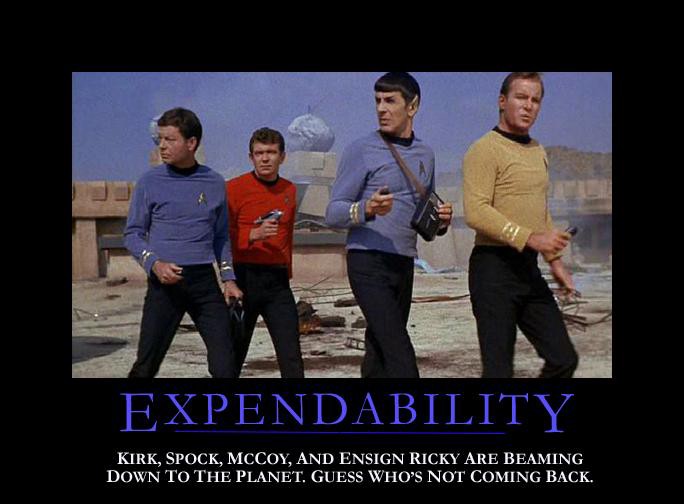

In Star Trek gold is the color of command, blue is the color of science and medicine, and red is operations. Red Shirts are engineers, communications, security, and everything else required to keep the ship running. They are also the first to die when things get tense.

Every organization contains people who, when given the chance, will drive improvement. They care about where they work and the people they work with. They want to make their lives, their co-workers’ lives, and the lives of their customers better. In Gene Kim’s “The Unicorn Project”, the Red Shirts are the cast of engineers and engineering managers who want to make things better. They know where things are broken and decide the best thing to do is to fix things instead of seeking greener pastures. They are passionate, at times subversive, change agents who conspire to improve things that result in larger improvements and better lives for everyone. These characters are based on real stories Gene collected from the DevOps community. In the book, there aren’t very many of them. All of them can comfortably sit at the bar after hours and discuss the next things they will try to fix. It’s a fragile rebellion that could fail if only 2–3 key players left. This is the reality of most grass-roots efforts.

I had a conversation with Gene Kim in 2018 discussing the work of pushing from the grassroots. I’ll never forget what he told me, “This work requires a certain level of not caring about the consequences”. That’s true. It’s risky to challenge the status quo; to “swim upstream”. It requires courage even when you believe that a senior executive approves of the work. It requires challenging people who are not used to being challenged; pushing just hard enough to not get “promoted to customer”. Because of this, there are not very many people willing to do it. However, when change is starting, those are the people who will passionately drive the day to day improvements needed to achieve the mission. If an executive talks about making things better, the Red Shirts are the people who execute. In some cases, they are even the people selling the value to the CIO or CTO. They are the people who will infect others with the mission and expand the effort. That infection doesn’t come from meetings, OKRs, and directives filtering down the leadership chain. It comes from the Red Shirts understanding the goals, seeing the problems, and coming up with solutions.

This work is hard, it’s stressful, and the number of people driven to do it is a tiny fraction of any organization. I’ve spoken to many Fortune 100 companies who need real change to happen to stay competitive. You could literally count their Red Shirts on your fingers. If you want lasting change, you’ll need to find a way to expand the Thin Red Line. Make improvement a valued activity in the culture and recognize those who try.

Written on February 8, 2021 by Bryan Finster.

Originally published on Medium