You Can't Measure Quality

6 minute read

“We want our teams to be more efficient and deliver higher quality!”

“We sure do, how will we measure it?”

The typical response is to apply a thin veneer of seemingly appropriate metrics, add a maturity model or two, and hope things get better. Whenever I hear of someone using code coverage to increase quality or using an “Agile maturity model” to improve team efficiency I know they need help. On the bright side, if you focus on the quality and drive down cycle times, then you get efficiency for free

First, let’s define some terms.

- Quality: Something the consumer finds useful.

- Efficiency: The ratio of the useful output in a process to the total resources expended.

- Cycle Time: The total time from the beginning to the end of a process.

Quality isn’t an abstract concept that can be predicted in isolation. Quality is the consumer finding the outcomes to be useful. Cycle time is how long it takes us to find out there are quality issues. By reducing the cycle time to get quality feedback, we reduce waste in the process and get efficiency for free.

You cannot measure quality. You can only measure the fact that poor quality exists. Does the consumer use your work? Are problems reported with your work?

This the 2017 MacBook Pro, Apple’s flagship laptop, until they started listening to their consumers again. I was waiting for this to come out in 2017 because I needed a new personal laptop. After it’s release, I went to the store, tried it out, and bought a refurbished 2016 model because the new one lacked quality. The keyboard lacked tactile feedback, it didn’t have the ESC key that all devs users use constantly, it didn’t have the ports I use when I travel for photography (dongles get lost in camera bags), and the touchpad is too big. I still use a mid-2014 for work and will until it dies or I can be assured I can get the new one with a better keyboard and an ESC key.

One of the basic behaviors required to establish a quality process is to establish a repeatable process to detect quality issues as rapidly as possible. In software, this is done using continuous delivery. Our first priority is to establish and maintain the ability to deliver to the consumer to find out how wrong we were. Our next priority is to deliver a small change and see if it’s we have quality problems and then continuously improve our ability to detect and prevent them in the future. The end-user isn’t the only consumer though. Every step in the process should reject poor quality.

We need to improve our tests

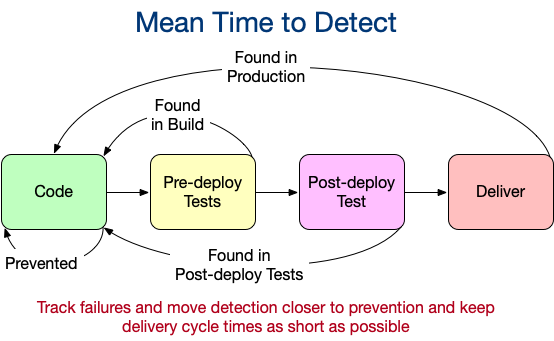

Code coverage is a terrible indicator of test quality. Code coverage reports how much code is exercised by test code while having nothing useful to say about the quality of those tests. We measure test quality by how ineffective the tests are from preventing defects from moving downstream. If we want to improve test quality, then we need to track the cycle time from commit to defect detection, Mean Time To Detect. The worst case is that they are found in production and that we deliver to production at the glacial pace of once a week or longer. The best case is that they are detected as soon as they are created using a mature CI process. So, we fix this by delivering more frequently (to reduce the number of defects per delivery) and we methodically measure and perform root cause analysis on defects to identify where the test suite can be improved to alert the developer much sooner. By methodically reducing the cycle time between defect creation and defect detection, testing quality improves. Tests will never prevent defects from occurring though and it’s critical we keep the cycle time from commit to delivery low to reduce the number and severity of production defects. Doing this reduces costs and improves efficiency.

We need good user stories

When I first had “Agile” inflicted upon me I was told that “Agile maturity” included having user stories with acceptance criteria and fewer than 13 story points. I am reasonably sure I’m not the only one who had “Agile” inflicted upon them by someone who was qualified because they passed a test after a 2-day class. So we created stories and they had bullet-pointed acceptance criteria but somehow things didn’t get better. We had a good “maturity score” though. Agile development isn’t a process, it’s an outcome. We were measuring processes, not the delivery. When I got on a team that was working towards continuous integration (master always deployable, changes integrate to master multiple times a day) we discovered it wasn’t enough to have a bullet-pointed list created by a product owner. “Good” acceptance criteria can’t be measured, but bad is easy to measure. How often is work blocked due to a lack of understanding? How often do developers ask for clarification? How often are code reviews rejected because of disagreements over functionality? Worst, how often are defects found in production and then re-classified as “enhancements” because what was delivered matched the bullet points? To improve this, we must improve the process of delivering acceptance criteria to the consumer of the acceptance criteria; the developer. BDD is an excellent process for this, BTW. We also need to track the cycle time to go from the story (the ask) to acceptance criteria (the goal) that the team fully understands and knows how to test. If I cannot test it, I cannot execute CI, and I can’t deliver with agility. If we reduce the time it takes to do this, then we also reduce the cost.

There are many steps required to go from idea to delivery. Each of those steps must be a quality gate. Each step needs to have entry acceptance criteria that can trigger the rejection of poor quality work from the previous step. Measure the reject rates, how long it took to find the issue, and how much it cost and your quality and efficiency will improve. Quality cannot be known in isolation. It can only be derived from the feedback from the consumer of your service or product. You don’t want to find out after working for a month that you have poor quality because your end-user refuses to use the work.

Written on May 14, 2020 by Bryan Finster.

Originally published on Medium