Designing Product Teams

7 minute read

What does a product team really looks like? You’ll hear lots of DevOps-y buzz words: “T-shaped people”, “cross-functional”, or “Two Pizza Team”. So, what is a viable product team and what are some common team anti-patterns?

First, a personal irritant of mine.

<rant>

Please stop saying "DevOps team." DevOps isn't a job. If you have a "DevOps team" doing release management or support

for you, spend time educating people on flow, feedback, and learning.

</rant>

Now that we’ve cleared that up, a product team has a few recognizable traits:

Cross-functional:

The team contains the skills and tools to allow them to build, deploy, monitor, and operate their portion of a product until the day when it is turned off. Team members have no individual responsibility for components, instead they pull work from the backlog in priority sequence. The team is not dependent on any outside dependencies, either technical, informational, or process, to deploy their product. If there are hand-offs then quality is reduced, MTTR will be too high, and the team will not feel the pride in ownership required for quality outcomes.

Anti-pattern: Release management team

Having another team responsible for deploying code prevents the product team from committing to deliverables and increases MTTR. It also makes release challenges opaque and prevents the team from improving their delivery flow effectively.

Anti-pattern: External QA

Outsourcing testing reduces quality and delays delivery. QA should be inherent in the team and should assist developers with test suite design to enable feedback from CI builds in less than 10 minutes.

Sole Source Ownership

The team has sole ownership and commit access to their repositories. This does not imply that the repositories should be private. Repositories should be openly readable unless there is a security risk. Teams need veto power over any change made by an outside contributor to make sure those changes meet the team’s standard of quality. Quality is owned by the team. Larger products should be divided among teams in a way that allows each team to have sole quality responsibility.

Anti-pattern: Shared source repositories

Everyone who has the ability to modify a repository directly is the de-factoteam. If that team is broken up into smaller “teams”, then process and communication drag will impact quality and the ability to deliver with agility. CI will not function and quality standards will be impossible to enforce. Delivery is delayed as process overhead increases in a failed attempt to overcome this structural problem.

Co-located in Time

The team works a schedule that enables them to effectively collaborate. They need not be co-located physically, but they must have enough overlap in working hours to allow a sustainable continuous integration process. Paul Hammant has an excellent article on evaluating your CI process. As the amount of overlapping working hours decreases, the communications lag between team members effectively silos the team. Team members will naturally divide into sub-teams who can collaborate together to deliver. Remote teams should be in frequent contact to avoid this fragmentation. The team needs to stabilize around working hours that support CI and protect value delivery.

Anti-pattern: Teams siloed in time

CI is the core of continuous delivery and requires a high degree of collaboration. The feedback loops needed to move value from idea to production must be as rapid as possible. If a team is divided in time in a way that they cannot effectively communicate instantly for a majority of their day, they become de-facto separate teams. These “teams” do not have sole quality ownership and delivery times will be extended as the “teams” adjust by adding process overhead that allows both “teams” to review the code. Over time, the sub-team cultures evolve independently and impact code review cycle time. Innersourcing processes can mitigate the quality issues by making only one of the teams a contributor instead of owners, but there is an increase in process overhead.

Responsible

The team has primary support responsibility. There are only two groups related to any product who care about the quality of that product, the end users and the product team who wakes up when things break. A high performing product team will ensure that their application has the resiliency, instrumentation, and alerting required to detect pending failure before the end user detects it.

Anti-pattern: Grenade Driven Development

Project teams require support teams to hand the project off to. Project teams are ephemeral. This type of development practice where code is developed and “thrown over the wall” for another team to support is destructive to the product and to the morale of the victim team. Product teams, by definition, have operational responsibility. They may not be the first people called, but only they can approve changes to their code. It’s up to them to make sure Operations has the information needed to alert the team effectively.

If the above principles are not true, it’s not a product team. It’s merely a “Pandemonium of Developers”.

Other considerations

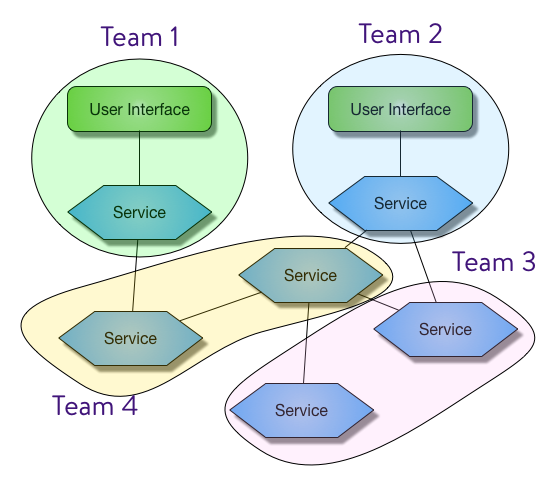

Having a cross-functional, co-located, responsible team with ownership is a good start, but it’s only part of the problem. To keep deliverables fast, cheap, and high quality, it’s important to minimize inter-team dependencies. Teams need to deliver independently in any sequence. This takes planning before we form a team. What is our desired architecture? Which functional domain will each team be responsible for? Things become more complicated here because, like many other things in application design, “it depends”. It also requires technical skills from the team with a focus on API management, Contract Driven Development, and an understanding of effective feature toggles.

Functional Domain

Domain Driven Design isn’t just a good idea, it’s an excellent way to align teams. As we decompose a product into sub-domains or as more functional domains emerge, we should be deliberate about assigning those capabilities. Things that should be tightly coupled should be assigned to the same team. Things that should be loosely coupled should be separated. If I’m using a back end for front end pattern, the UI and the service should absolutely be on the same team. Otherwise, the dependency drag for implementing any change will result in glacial delivery. If I also need the capability of tracking account transactions, I can easily assign that to another team and allow them to develop that solution independently. In that case, we assign the capability based on capacity planning.

Desired Architecture

The impact of placing two capabilities on one team is that they will tend to become entangled. That can be as simple as becoming a single deployable or as complicated as functionality drifting across interface boundaries. If the capabilities are closely related, this can be an advantage. Combining them into fewer deployable artifacts can result in less operational overhead. Microservices aren’t always the answer (avoid Conference Driven Development). However, if the capabilities are unrelated and things start to merge, you’ll need to invest in marinara before you tackle refactoring the resulting spaghetti.

Vertical or Horizontal?

“Do we create a UI team and one or more service teams? Do we divide the UI across teams?”

Take a look at your wireframes. Are there discrete functional domains represented in the UI? A component for showing stock prices, one for showing account balances, and another for scheduling bill payments? Those can easily be developed in functional pillars and developed and deployed independently. Aligning teams to a business domain instead of the tech stack removes hard dependencies to feature delivery and allows the teams to become truly full-stack. Not only do the know the full technical stack, but they also own the entire problem they are solving. They know the business stack.

This isn’t always possible and it does sometimes make sense to have a UI team, but that should be a fallback position. Better outcomes come from a team who is expert in their business domain.

Is it really a team?

Product teams deliver quality. They care about their team, their product, and their ability to meet the needs of the customer. Random assemblages of developers taking orders do not. It falls to technical leaders to know the difference and to optimize teams for delivering business value. Grow your product teams. They are a strategic business asset that are required to compete in the current market. Happy developers with tight collaboration who are experts in their problem space can work miracles. “Development resources” do not.

If this post was helpful, please click the clap 👏 button below a few times to show your support for the author! ⬇

Written on February 7, 2019 by Bryan Finster.

Originally published on Medium